Q: How do you teach your student to ask for a “work” break versus a “movement” break?

Authors: Alexis Bondy, BCBA, and Lauren Kryzak, BCBA-D

Great question! First, let’s consider why this is such an important consideration. In ABA, behavior is defined based on its function, not just its form (or maybe not form at all!). In other words, we are typically more interested in why a behavior occurs, than what it looks like. This question perfectly highlights that a student might do the same behavior (e.g., asking for a break), but for different reasons (i.e., functions). If we consider behavior only based on form, we may not provide the correct consequences that the student is asking for. This can accidentally result in a decrease in requesting (since it’s not getting the student what s/he wants anyway) and/or an increase in problem behavior.

Consider how often in your work day you give yourself a break for different reasons and to do different things. Sometimes it is a break from doing work (e.g., staring off into space, checking text messages) and sometimes it is a break to get something (e.g., speak to a co-worker, get coffee, take a bathroom break). How we take a break should be directly related to why we take a break. Our students should be given similar opportunities to take breaks – for various reasons – from assigned activities and tasks.

Next, let’s consider “movement” breaks.

For students who are leaving (or attempts to leave) their work area and then immediately engage in activity (e.g., jumping, arm flapping, dancing, running), consider teaching the student to request a movement break. In order to teach any functional communication response, it is very important that the language used be individualized and based on the student’s current communication repertoire and skill ability. For students with a limited vocabulary, keep replacement phrases short and simple. For example, teaching the student to say, “get up” to gain access to a movement break. For students who have no vocal language, consider teaching the student to request with a picture. The target functional communication response can be specific to the activity. Let’s say your student enjoys taking walks, then teach him to request “walking”, rather than teaching him to ask for a “movement break”.

In general, requests for movement breaks can be taught through mand training and transferring stimulus control from a prompt to the student’s motivation. For many students using a visual support will decrease the response effort and may act as a prompt, that is faded to a cue, which may ultimately be left in the student’s environment.

Next, let’s consider “work” breaks.

If Antecedent-Behavior-Consequence (ABC) data suggests that a student engages in problem behavior maintained by escape or avoidance of completing required tasks, teaching the student to request a “work” break as an appropriate alternative behavior may decrease future problem behavior.

How to start? Prompt the student to request a work break after completing an easy, high-probability demand (in the absence of problem behavior).

Be sure to use a topographically different response than the movement break – such as “can I have a minute?”, or “I’m done”. Provide the student with activity options that are different than the movement break activities – such as sitting in a bean bag, reading a book, or putting their head on their desk.

As the student responds reliably to the prompt, fade it until the student independently requests a work break. Begin to grant the request – when the student is calm – intermittently. This means that sometimes that the student makes the “work break” request, the teacher denies it and makes the student continue with their current activity. If this is difficult for the student, consider systematically increasing the tolerance of compliance (see Ghaemmaghami, Hanley, & Jessel, 2016).

Simultaneously, begin to prompt the student to make the “work break” request when precursor – or low level – problem behavior occur. For example, if a student tends to call out before getting up from their seat, when the student calls out, prompt him/her to request a work break. Differentially reinforce and fade prompts until the student is independently requesting work breaks.

Be careful! Providing a break as a consequence after problem behavior can cause problem behavior to increase. It is important to teach this functional communication response before the student emits problem behavior. If a work break is provided immediately after (or during) problem behavior, it is possible that the break will reinforce the problem behavior. If the student does emit problem behavior, try to have the student engage in some compliance response and then prompt the work break request. Provide high quality work breaks (e.g., longer break, higher quality) for independent requests and lower quality work breaks for prompted requests (e.g., shorter, lower quality).

In general, provide the student with a means to communicate each type of request and teach the student in which context each request will be granted.

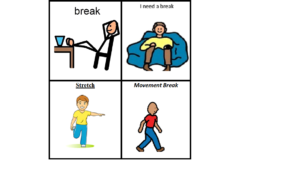

Below are some picture ideas for both “work” breaks and “movement” breaks:

If a student has a visual schedule, teachers can add movement breaks directly on the schedule. This can strengthen the association between the corresponding visuals and consequences. The visual may represent a specific activity, such as going for a walk, or it could be a generic visual which corresponds with a “movement” choice board allowing the student to choose from various activities, such as to go for a walk, toss a ball with a partner, or do jumping jacks. Having a variety of activities for the student to choose will decrease likelihood of him/her getting bored with the same repeated activity.

References:

Dillon, S. R., Adams, D., Goudy, L., Bittner, M., & McNamara, S. (2017). Evaluating Exercise as evidence-based practice for individuals with autism spectrum disorder. Frontiers in public health, 4, 290.

Durand, V. M., & Carr, E. G. (1992). An analysis of maintenance following functional communication training. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 25, 777–794

Ghaemmaghami, M., Hanley, G. P., & Jessel, J. (2016). Contingencies promote delay tolerance. Journal of applied behavior analysis, 49(3), 548-575.

Hagopian, L. P., Fisher, W. W., Sullivan, M. T., Acquisto, J., & LeBlanc, L. A. (1998). Effectiveness of functional communication training with and without extinction and punishment: a summary of 21 inpatient cases. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 31(2), 211–235. http://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.1998.31-211

Leave a Reply